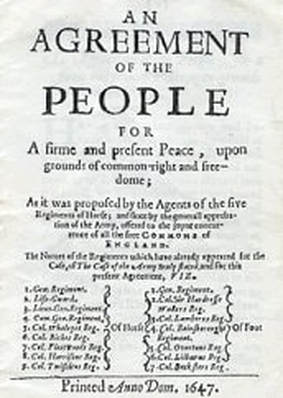

''Only very slowly and late have men come to realize that Whether you call it the English Civil War or the English Revolution is a matter of politics. But either way, it is not one but three separate and distinct campaigns, none of which are exclusively English or even restricted to England: they also affect Scotland, Wales and – profoundly – Ireland. The first lasts from 1642 to 1646 and is essentially between the king, Charles I, and parliament; the second addresses unfinished business from the first, starting in December 1647 when Charles negotiates a treaty with the Scots, promising to establish Presbyterianism in England in return for a Scottish invasion of England; the third, from 1649 to 1651, is concerned with Charles II taking advantage of assorted dissident forces from Ireland and Scotland rising up against parliament. In this last campaign, Charles II rules briefly as King of the Scots but is defeated over and over again before the final humiliation at Worcester and his escape to Normandy on the 16th October. But the English Revolution or Civil War is not our primary concern here, except in so far as it is the context and backdrop for series of political, constitutional and social movements which changed the nature of the country for good, but – some believe – could have gone a great deal further. It is these movements that we will concentrate on. The Levellers and the Diggers – AKA The True Levellers. In our search for a single person who epitomizes the movement, it’s a toss up between Gerard Winstanley and John ‘Freeborn’ (his epithet) Lilburne. I’m going for Freeborn John, who is also known as “Honest John” after his oft-proclaimed statement that “honesty is the best policy”, because he’s at the heart of it all. Before, during and after the wars. From beginning to end, Lilburne is central. He's in the army, on the streets, in the stocks, in court, in the Star Chamber. He's tried for treason when captured by the Royalists and tried twice for his life under the Commonwealth. He's imprisoned under both the king and Cromwell. He’s everywhere. And everywhere he is leading, orating, arguing, writing, printing, campaigning. He writes more than 80 pamphlets - against intolerance, censorship, trade restrictions and conscription, and for rule of law, separation of powers, a written constitution and freedom – of religion, of speech, of trade, of the press. It was said of him that: “If the world was emptied of all but John Lilburne, Lilburne would quarrel with John, and John with Lilburne". And this is from a friend, the lawyer, republican and regicide Henry Martin! The same notion is repeated in a famous epitaph: Is John departed, and is Lilburn gone! Farewel to both, to Lilburn and to John … But lay John here, lay Lilburn here about, For if they ever meet they will fal out The trope endures to this day. And it is worth quoting, because his “quarrels”, his grievances and, fundamentally his constitutional views, are what distinguishes him. His entire life is a a powerful combination of the personal and the political. So personal that his ideas and principles, his politics, were changed, conceived even, by his imprisonment and the injustices he suffered. A crucial example is his view of liberty, which changes as a response to his “sufferings”. Initially, he sees it as a political and idealized abstraction but, arrested and imprisoned, he comes to adopts a more negative conception, akin to but a few years earlier than that of Hobbes in Leviathan, defining it by what it is not rather than what it is. In the words of D. Alan Orr, for Lilburne, liberty becomes "more the absence of a condition of dependence on the will of another - a condition of slavery - than simply the absence of external physical impediment to act as he desired". A brief life And it is a very brief life, because he dies in 1657, in his early 40s. Born in Sunderland (or maybe Greenwich – both are recorded) in 1615 (or maybe 1614), the third son of a country gentleman, he is sent to London in 1630 to serve an apprenticeship with a wholesale clothier named Thomas Hewson. He serves six years as an apprentice, and they are formative, because Hewson is a Puritan with extensive connections to the Puritan movement and Lilburne appears to spend at least as much time studying Puritan teachings as his apprenticeship. He immerses himself in the Bible, Foxe's Book of Martyrs and the writings of the Puritan divines. And he meets leading Puritans such as the physician John Bastwick, recently having had his ears cut off by Archbishop Laud, not personally but at his instruction, for criticizing the Church. Lilburne organizes the printing of Bastwick’s book, Letany, and on his return to England, is arrested for doing so, imprisoned in the Gatehouse, and appears before the Star Chamber on a charge of unlawfully publishing “libelous and seditious books”. This is the first time Lilburne comes to the attention of the people. In the Star Chamber, he declares himself “freeborn”. Arguing that the prosecution is therefore unlawful, he refuses to take the oath or answer any questions. Inevitably, he is found guilty and sentenced to be whipped, pilloried and imprisoned until he confesses his guilt. The brutal sentence is carried out on 18th April 1637, and Lilburne makes it a religious epiphany, calling it “my wedding day, in which I was married to the Lord Jesus Christ; for now I know hee loves me, in that hee hath bestowed so rich apparel upon mee, and counted mee worthy to suffer for his sake”. The people of London turn out to support him in droves but despite the popular support, he remains in prison for three years, spending his time writing a series of pamphlets complaining about the injustice of his treatment. (As Diane Parkin-Speer notes, throughout his public career, “Lilburne always seems to be in prison and manages somehow to get his grievances printed”.) But his ‘freeborn’ epithet and the pamphlets keep him in the public eye and, when Charles is forced to summon parliament in November 1640, Cromwell is the man who denounces the sentence and the process itself. Parliament orders his release. Cometh the hour, cometh the man. He is immediately involved in the new spirit of protest in the capital, haranguing the crowds at the execution of the Earl of Stafford and leading an apprentice’s riot against the king’s guards. But he also finds time to marry Elizabeth Dowell, a political and religious soul-mate, with whom – despite his absences in the army, on trial and in prison - he manages to have ten children. It is Elizabeth who is instrumental in saving his life in 1642. He is quick to enlist at the outbreak of hostilities, fights at Edgehill but is taken prisoner at Brentford and at the royalist headquarters in Oxford, is charged with treason and rebellion. With execution the only conceivable outcome, Elizabeth petitions parliament, provoking an emergency debate at which parliament threatens to execute royalist prisoners in retaliation, and – despite being heavily pregnant – takes parliament’s message to Oxford herself. The charges are dropped, an admission by the king that captured parliamentarians are prisoners of war rather than treacherous subjects. Exchanged for a royalist officer in May 1643, he is commissioned as a Major with help from Cromwell and promoted to Lieutenant Colonel a year later, fighting with distinction at Marston Moor and accepting the surrender of Tickhill Castle without a shot being fired, against the orders of his commanding officer, the Earl of Manchester. Then he returns to his ‘quarrels’. He resigns his commission after refusing to sign the Solemn League and Covenant, a requirement after Parliament makes an alliance with the Scots. He writes a pamphlet defending freedom of conscience over the religious orthodoxy of former friends and supporters William Prynne and John Bastwick. And he’s in Newgate prison for four months after criticizing MPs for living in comfort while common soldiers fought and died. Meanwhile, he is pursuing the promised compensation for his persecution by the Star Chamber and in July 1645, he is back in Newgate, this time for criticizing the Speaker of the Commons. But, as ever, he manages to write a succession of pamphlets of greater or less vitriol and get them published by friends. In these, he describes injustices committed against him personally, attacking corruption, profiteering, monopolies and excise, and calling for freedom of the press. One of the key texts is the snappily-titled “England’s Birthright Justified Against all Arbitrary Usurpations, whether Regall or Parliamentary or under what Vizor soever.” He argues for laws written in English, and trial only after charges are filed, refer to known laws and when the defendant can confront the accuser and present a defence. Further, noting that length of service made MPs more corrupt, he calls for annual elections and universal male suffrage. But he hasn’t yet finished. Released in October, he writes The Just Man’s Justification against the House of Lords, who promptly send him back to Newgate, where he writes another pamphlet , this one entitled The Freeman’s Freedom Vindicated. And he has massive support throughout the country and particularly amongst his close friends and fellow-pamphleteers. One of these is his printer, Richard Overton, who is imprisoned for writing pamphlets in defence of Lilburne writing pamphlets. What does he do? He writes a pamphlet, entitled – wait for it – An Arrow against all tyrants and tyranny, shot from the prison of `Newgate into the Prerogative Bowels of the Arbitrary House of Lords: “To every individual in nature is given an individual property by nature, not to be invaded or usurped by any. For everyone as he is himself, so he hath a self propriety, else could he not be himself.” 'We, the free people of England' The arrow strikes its target. Essentially, Parliament at this point – and it’s not solely the Lords – is lining up against “the most popular man in England”, who is keeping in touch with the army Agitators throughout 1647. So much so that his are the ideas and much of the prose in the Leveller manifesto, An Agreement of the Free People of England, which talks of an England which has “for some yeares by-past, drunk deep of the Cup of misery and sorrow”. The four imprisoned Leveller leaders - Lilburne and Overton, together with William Walwyn and Thomas Prince declare: “We the free people of England, to whom God hath given hearts, means and opportunity to effect the same, do with submission to his wisdom, in his name, and desiring the equity thereof may to his praise and glory; Agree to ascertain our Government, to abolish all arbitrary Power, and to set bounds and limits both to our Supreme, and all Subordinate Authority, and remove all known Grievances. “And accordingly do declare and publish to all the world, that we are agreed as followeth.” What ‘followeth’ are thirty articles, demanding a range of reforms from a new parliament elected by (almost) universal manhood suffrage to economic reform and abolishing imprisonment for debt; and more. Noteworthy is Article X which deals with religious tolerance. Parliament will have no powers in religious matters for government intrusion in the past has caused “distractions and heart burnings in all ages”, resulting in “persecution and molestation”. (As Carl Watner points out, “Theirs is the distinction of being the first movement in the modern world to call for a secular republic.”) Article XVI bans self-incrimination in judicial proceedings and is the basis for the US 5th amendment. And Article XXVII strikes to the heart of Cromwell’s military dictatorship. Civil authority is to be supreme over the military. The final paragraph sets the revolutionary proposals in a religious perspective: “Thus, as becometh a free People, thankfull unto God for this blessed opportunity, and desirous to make use thereof to his glory, in taking off every yoak, removing every burthen, in delivering the captive, and setting the oppressed free; we have in all the particular Heads forementioned, done as we would be done unto, and as we trust in God will abolish all occasion of offence and discord, and produce the lasting Peace and Prosperity of this Common wealth.” Which is a moderate and reasonable conclusion to a revolutionary tract. And it does not stop Cromwell calling the famous Putney Debates to a halt when the Agreement becomes the central topic of discussion.. He realizes that the radical ideas expressed in the manifesto will undermine the discipline of the highly, even harshly, disciplined New Model Army. Nevertheless, they form the basis of a series of negotiations between the Grandees and the levelers, and this time Lilburne is there, trying to persuade the Grandees to accept the Agreement before Charles is tried – thus giving any trial a legitimacy according to a new constitution. He loses the argument, refuses a nomination to the High Court of Justice, and absents himself from the trial and the execution. Another pamphlet – England’s New Chains Discovered – greets the new Republican government, which charges Lilburne and other Leveller leaders with high treason. Defending himself, he is acquitted but kept in prison until public and parliamentary pressure eventually secures his release. He wins election as a Councillor for the City of London but the election is declared void. He considers a career in law, but he’s blocked by the Inner Temple. He loses a property dispute, is fined and banished under threat of death, returning when Cromwell ejects the Rump parliament. He claims that his banishment is now void. The Old Bailey is packed to hear his arguments and see him found not guilty. (In fact, the jury’s verdict is that “John Lilburne is not guilty of any crime worthy of death”.) But the government, breaking the right of habeus corpus, orders that he should be held in prison indefinitely. In fact, he is held in several prisons, ending up at Dover Castle. Elizabeth and the children move nearby and he is granted daily parole to visit them. He becomes a Quaker and writes one final pamphlet, The Resurrection of John Lilburne, in which he announces that he is giving up politics. He dies on 29 August 1657, after catching a fever whilst visiting his wife shortly before she gives birth to their 10th child. He was just 42 (or maybe 43). “I shall leave this testimony behind me: that I died for the Laws and Liberties of this nation.” Is Lilburne a Leveller? Lilburne hates the term and its connotations. He comes to accept it only reluctantly. And of course the Diggers are the True Levellers. But levelling is not what Lilburne’s Levellers are about. For him, the two foundations of the state should be liberty and property, “which are quite opposite to community and levelling”. “This conceit of Levelling of property and Magistracy” he writes, “is so ridiculous and foolish an opinion, as no man of brains, reason, or ingenuity, can be imagined such a sot as to maintain such a principle. because it would, if practiced destroy not only any industry in the world, but raze the very foundation of generation, and of subsistence or being of one man by another. For as industry and valour by which the societies of mankind are maintained and preserved, who will take the pains for that which when he hath gotten is not his own, but which must equally shared in, by every lazy, simple, dronish sot? or who will fight for that, wherein he hath no other interest, but such as must be subject to the will and pleasure of another, yea of every coward and base low spirited fellow, that in his sitting still must share in common with a valiant man in all his brave and noble achievement? The ancient encouragement to men that were to defend their Country was this: that they were to hazard their persons for that which was their own, to wit, their own wives, their own children, their own Estates. And this, give me leave to say, and that in truth, that those men in England, that are most branded with the name of Levellers, are of all in that Nation, most free from any design of Levelling, in the sense we have spoken of.” Significantly, this ethic extends beyond England. The Leveller hostility to Cromwell’s imperialistic subjugation and occupation of Ireland is based on a belief that the individual Irishman has as much right to his own land as the individual Englishman. The Irish may be catholic, foreign, but they are fellow men and , as such, entitled to their own liberty and property. The thinking is based on common law and the “law of nature”, and it pre-dates the Norman invasion. Christopher Hill is good on this, showing how Lilburne stops quoting magna carte and Coke’s Institutes, in favour of natural rights and natural laws. In his 1646 pamphlet, The Just man’s Justification, Lilburne argues that “the greatest mischiefe of all, and the oppressing bondage of England ever since the Norman yoke is this, I must be tried before you by a law (called the Common law) that I know not, nor I thinke no man else, neither do I know where to find it, or reade it”. Man can only be subject to anything or anyone with his own informed consent. (Hence his railings against the use of Latin, which neither he nor “one of a thousand of my native Country men” can understand.) Without consent, government is not “magistracy” but tyranny. Thus, resistance to the King is not only acceptable but a duty. And when Cromwell and Parliament demonstrate they, too, are acting tyrannically, they must also be resisted and overthrown. The law of nature also guarantees property rights. Henry Ireton, Cromwell’s son-in-law and spokesman at the Putney Debates, claims that the Levellers would destroy all property. But the Levellers responded that “yet really properties are the foundations of constitutions, and not constitutions of property. For if so be there no constitutions, yet the law of nature does give a principle for every man to have a property of what he has or may have which is not another man’s. This natural right of property is the ground of mine and thine.” So not a Leveller in the sense of redistributing wealth and property from rich to poor, as Ireton and Cromwell would have us believe. And not an anarchist, either, though he and the Levellers are accused of attempting to set up “an utopian anarchy of the promiscuous multitude”. It is true that the Levellers argue for the right to refuse commands incompatible with his individual conscience or concept of reason or justice – this is how liberty is created, protected and guaranteed. But it is not anarchistic. Indeed, Walwyn makes it clear that “we are for Government and against Popular Confusion” and that “though Tyranny is excessively bad, yet of the two extremes, Confusion is the worst. “Tis somewhat a strange consequence to infer that because we have labored so earnestly for a good Government, therefore we would have none at all; because we would have the dead and exorbitant Branches pruned, and better sciens grafted, therefore we would pluck the Tree up by the roots.” So not leveller, not anarchist and, with the primacy of the individual, not socialist either. So what is he? Who is John Lilburne? A freeborn man. An honest man. A writer. An orator. A barrack room lawyer. A democrat and constitutional reformer, many of whose proposals are now constitutionally in force, in the UK, in the US and throughout the democratic world. Just as he predicted. “Though we fail” he said, “our truths prosper”. Vertical Divider

|