"All plots tend to move deathward. This is the nature of plots. Political plots, terrorist plots, lovers' plots, narrative plots, plots that are part of children's games. We edge nearer death every time we plot. It's like a contract that all must sign." Vertical Divider

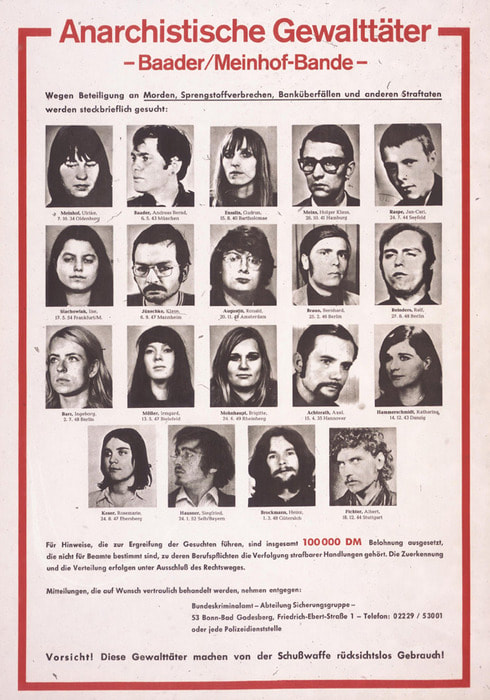

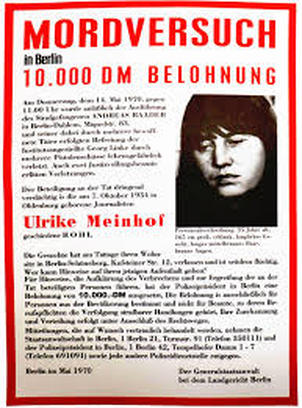

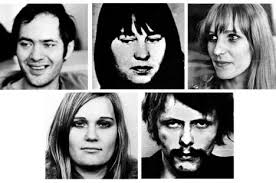

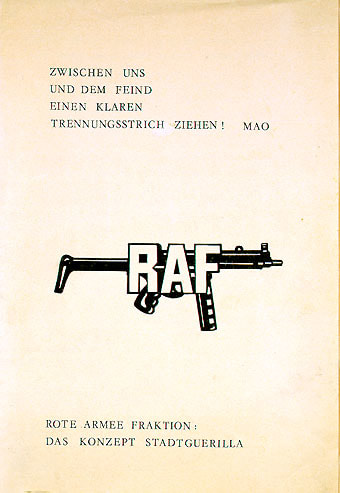

A ‘faction’ is a small dissenting group within a larger party; a ‘fraction’ is part of a whole. It’s an important distinction, which was crucial to the RAF – the Rote Armee Fraktion – from the very beginning in 1970 to that final communiqué in 1998: “The urban guerrilla in the form of the RAF is now history.” If it is true, as the RAF claimed, that their very existence was a success, then the ‘fraction’ known more commonly as the Baader-Meinhof Group or Gang was successful in this objective at least. No less than three separate ‘generations’ of the RAF coruscated before that final communiqué. It makes telling their story a complicated task – not for nothing is Stefan Aust’s definitive history entitled The Baader-Meinhof Complex. My focus will be on personal relations and political philosophy rather than an account of ‘actions’. But even with this self-imposed limit, even though this is merely a fraction of the whole, there is much to include and even more to omit. Compared with other, similar organizations (The Weather Underground in the US, the Red Brigades in Italy, the 17 November Revolutionary Organization in Greece, the Angry Brigade in the UK, Action Directe in France), the RAF lasted longer, were a larger organization, committed more acts, were more violent, were responsible for more deaths, and paradoxically, garnered greater popular support. But by the time of the 1998 communiqué, many of the original, founding, group are long dead by their own hand or, as some remain convinced, by the state. So it's on this first group, this first generation of the RAF, that I will concentrate: Andreas Baader, Gudrun Ensslin, Jan-Carl Raspe and Helger Meins. Plus, primarily, Ulrike Meinhof herself (whose journey I believe to be the most interesting of the group, perhaps because we have both undergone the trauma of brain surgery, but really because she is far the most complex and nuanced character, a fox in Isaiah Berlin's party game, who is committed to becoming, through her writing, a hedgehog). I will bring the essay to an end with her death on the night of the 8th/9th May 1976, rather than with the suicides of the other first generation members or, the very end in 1998. We start, uncharacteristically, at the beginning, when Meinhof is a young left-wing journalist, the editor of the widely circulated Konkret! magazine, and Baader is, well, a juvenile delinquent. A charismatic and over-age juvenile delinquent to be sure, but a juvenile delinquent nonetheless. Despite the popular name, the name a hostile press gives to them, the story really begins not with the meeting of Baader and Meinhof, but when Ulrike met Gudrun. Back in 1964, The Observer’s correspondent Neil Ascherson interviewed Ulrike. “I thought her tender and vulnerable” he reports. “I found her in a suburban house, a nervous, pretty woman of 30 with two blonde little girls rolling round her feet … She was having trouble, she confessed with the Socialist Students’ League (SDS), which was trying to cast her out for lack of Marxist vigour. They despised her pacifism. ‘They call me a peace-loving egg-pancake’ she said sadly.” The ‘suburban’ house, by the way, is a pre-First World War mansion in Blankenese, the most exclusive and expensive suburb in Hamburg.) Meanwhile, Gudrun Ennslin, “the daughter of a deeply serious and compassionate Lutheran minister in Swabia” who has come to radical socialist politics whilst spending a year at Mthodist College in the United States. When a student is shot dead at a demonstration against the Shah of Persia (Baader misses it because he was in borstal for stealing a motorbike) and Rudi Dutschke, “the Danton of the SDS”, is shot by a man screaming ‘Communist swine’, Ensslin develops the ‘no compromise’ position which would later become the over-riding principle of the RAF. As many have noted, the RAF was really the Baader-Ensslin Gang. Gunter Grass, who knew Ensslin at this time, said that “she was idealistic, with an inborn loathing of any compromise. She had a yearning for the Absolute, the perfect solution.” She is, writes Jillian Becker in Hitler’s Children, “made to measure” for Ulrike, “the true crusade leader of Ulrike’s aspirations”. After all, she is already in jail for taking violent action. And, by embracing Baader, she is also embracing his “daredevilry” and adding that into her mix. So when Ulrike interviews Gudrun, in jail for arson, in the spring of 1968, she is struck, impressed, in awe even by her passion, commitment and, although six years younger, her record of resistance. It is not quite an epiphany. Ulrike is moving, tentatively of course, Ulrike being Ulrike, in this direction. But now she begins to move more quickly, although still requiring emotional support at each stage. Within six months, she divorces her husband, father of her children and co-editor of Konkret! Within a year, she quits Konkret! Soon, she will send her two small daughters into exile in a hippy commune. And throughout this time, her prose becomes more and more revolutionary. But she is still an armchair activist – attending a demonstration against the right wing Springer publishing house, she frets about where to park her car, worried that it may be considered part of a barricade and damaged. She has a large, luxurious apartment in Berlin, a centre of radical politics and discussion from a hotch-potch of the left. But it's still primarily discussion. Until, in the spring of 1970, the now fugitives Baader and Ensslin arrive. The great leap This time, it takes. It gels. When Ensslin tells her, she should stop talking and writing, and do something, she agrees - in principle. But when Baader is re-arrested, and Ulrike’s new best friend pleads - she really pleads, she can't live, exist, without her 'Baby' - for help in organizing his escape, she agrees. Not just in principle. This time in practice. The plan involves a visit by Ulrike in the role of editor and journalist to discuss a possible book with Baader about ‘German youth’. On May 14, she arrives at the Institute for Social Issues where, watched by a guard, the two affect to discuss the book as an armed and disguised Ennslin, two women and a man enter the building. They free Baader but in the process shoot the guard and a member of staff. They escape by leaping through a window and Jillian Becker is clear that this is the turning point in Ulrike’s life. Up to this point, anyway. Her assessment: “For Ulrike Meinhof, her leap with Baader out of the library in Dahlem was an act as irreversible as suicide; and for a while at least it did very well instead. To leap out of an old unsatisfactory life into a new, of excitement and urgent purpose, romantically at pitch and in peril, and with a new name, was virtually – so she must have hoped – to lose the old identity and to leave the old melancholy separateness behind; for the new identity was that of the group.” The group go underground, and a couple of weeks later issue their first communiqué as a group. It announces the formation of the Rote Armee Fraktion or RAF. Two points to make about this self-description. First, the Red Army is the Soviet Army, the nemesis of the Third Reich. Second, RAF is the Royal Air Force, which bombed Germany night after night for the last years of the war. It may not be ideological, but it is certainly provocative to a generation which suffered from both. We are to wait almost a year before the first communiqué with any attempt at ideological explanation is released. By which time of course, the RAF has trained in Jordan with the PLO – during which Baader characterises Ulrike as “useless”; has established safe houses and stockpiles of weapons throughout West Germany; robbed hundreds of banks for thousands of marks; and lost several of its members to police arrest. One of these is Horst Mahler, who makes a bizarre journey from lawyer to revolutionary socialist terrorist to neo-fascist and holocaust denier. But at this time, he is playing at being the RAF’s Lenin, writing from his prison cell a 70 page treatise entitled On Armed Struggle in Western Europe. But Baader, Ensslin and Meinhof reject it out of hand. Aust quotes their response: “It has nothing to do with us. As a concept of guerrilla action it’s as inflated as a game of cowboys and Indians”. But it does prompt them to commission Ulrike to write an authentic manifesto on behalf of the RAF. The Concept of the Urban Guerrilla appears on 1st of April 1971 - the irony is lost on the RAF – and draws heavily on Mao and, to a lesser extent, Lenin, Regis Debray, the Italian Il Manifesto movement and others. It is, however, very specific to the West German situation and, at times, very personal: much is a bitter reaction to criticism and perceived slights from others on the left. “We have nothing to do with these chatterers” she proclaims, “for whom the anti-imperialist fight is conducted at coffee parties.” There is, however, some serious political philosophy - and not all from Mao and Lenin. Offering “concrete answers to concrete questions”, Ulrike argues for “the primacy of praxis”. “Without political practice, reading capital is nothing more than bourgeois study. Without political practice, political programmes are just so much twaddle. Without political practice, proletarian internationalism is only hot air. Adopting a proletarian position in theory implies putting it into practice. “The Red Army Fraction asserts the primacy of practice. Whether it is right to organize armed resistance now, depends on whether it is possible, and whether it is possible can only be determined in practice.” From here, she develops some definitions of the urban guerrilla: “The urban guerrilla is based on facing facts, not making excuses for them.” “The urban guerrilla is a weapon of class struggle.” “The urban guerrilla struggle means not being demoralized by the violence of the system.” “The urban guerrilla aims to destroy certain aspects of the state structure, and to destroy the myth of state omnipotence and invulnerability.” And: “The urban guerrilla requires the organization of an illegal structure, including safe houses, weapons, cars, and documents. What needs to be known beyond that, we are always ready to tell anyone who wants to participate in the guerrilla struggle. We don’t know that much yet, but we know a little bit.” At the end, “the urban guerrilla” has become “The Red Army Fraction”. As in: “The Red Army Fraction” organizes illegality as an offensive position for revolutionary intervention.” And “The Red Army Fraction creates the connection between legal and illegal struggle, between national struggle and international struggle, between political struggle and armed struggle, between the strategic and tactical aspects of the international communist movement”. The communiqué is a strong and assertive in tone. She is, or appears, confident in and of herself. But she is writing not for herself, but on behalf of the group, the collective. Baader and Ensslin are strong and assertive, self-confident, arrogant even. Which means the RAF is the same. But Ulrike is not. The communiqué is peppered with whinges, resentments. “Some people” she writes, “distort even the smallest details”; “spread untruths about us”; “want to make it look like they are “in the know”; Mahler’s arrest was down to our carelessness, but to “betrayal”. It’s not paranoid, but it’s close, you might think. And it reflects the situation within the group, where Ulrike’s moral stances are ridiculed by her comrades. And her lack of self-confidence means that she lacks influence in a group dominated by Baader and Ensslin, who repeatedly criticize Ulrike’s lack of practical competence. Baader had called her "useless" in Jordan. Now, she shows the same uselessness in everyday revolutionary activity. She is reported to have broken the wheel of a car she was stealing; she came back from a bank robbery with a mere 8,500 DM, having left a bag containing 95,000DM behind; she confuses the addresses on parcels containing blank passports and identity cards. Moreover, her tendency to over-analyse every situation and impose a political dimension to every discussion meant that her comrades were reluctant to engage with her, forcing her increasingly outside the group for intellectual solace. One argument, during Christmas 1970 in Stuttgart, was fundamental. Ulrike argues that the RAF was too disorganized and that insufficient preparation was made for their actions. Baader responds that mistakes were individual mistakes, not the result of the group structure. (An echo, a parallel, here of the Weather’s John Jacobs (JJ) arguing a similar point after the townhouse explosion. But this time, the Baader/Jacobs line prevails.) In Stuttgart, it marks a permanent change in the relationship between Ulrike and the remaining members. And if Ulrike is increasingly isolated within the RAF, she was also under pressure from those who sympathize from outside the group. In November 1971, Konkret!, the magazine of which she was once editor-in-chief, publishes a letter from Ulrike’s step-mother, Renate Riemeck. Headed, “Give Up, Ulrike!”, it is clearly written by someone who knows Ulrike intimately. It flatters her – she was “too intelligent and reasonable to confuse anti-authoritarian rebelliousness with the beginning of a broad revolution”. It questions her – “who understands the political and moral impulse behind your actions? A spirit of sacrifice and the readiness to face death become ends in themselves if one cannot make them understood.” It chastises her – “You must correct yourselves.” And it appeals to her better nature – “I do not know how far your own influence within the group extends, how far your friends are amenable to rational considerations. But you should try to measure up the chances of an urban guerrilla movement in the federal Republic against the social reality of this country. “You can do that, Ulrike.” It took Ulrike three weeks to respond. When she does, she re-writes Riemeck’s latter in the form of a latter from a “slave mother” beseeching her daughter to accept her lot, promising that she could become an overseer if she accepted her life as a slave and behaved in obedience to the authorities. With this response, she cuts herself off from family and friends. She is, effectively, alone, but determined to continue “the long struggle” even as she has doubts about the strategy and is, some friends say, “depressed”. And there are many actions over which to ponder. A police officer is killed during a bank raid in December 1971. The pace picks up in 1972, with bombs exploded in US Army bases in Frankfurt and Heidelberg, in a police station in Augsburg, the Criminal Investigation Office in Munich, the car of a federal judge and the Axel Springer building in Hamburg. In June that year, police officers raid an apartment they believed harboured members of the RAF. Ulrike is arrested, but her appearance – thin and sick – means that they doubt the identification. To verify that this is indeed Ulrike, they forcibly anaesthetize her in order to take head X-rays. They are looking for the silver clamp inserted ten years previously during a brain operation. Her identity is confirmed. It is Ulrike Meinhof. And the following day, she is taken to the ‘dead section’ of Köln-Ossendorf, where she has no contact with other inmates and is allowed to see family members for just 30 minutes at a time, once every two weeks. “The feeling that your head is exploding. The feeling that the top of your skull must be going to split and come off. The feeling of your spinal cord being pressed into your brain. The feeling that the cell is moving ... “Furious aggression for which there is no outlet. That’s the worst thing. A clear awareness that your chance of survival is nil. Utter failure to communicate that. Visits leave no trace behind them. The feeling that space and time interlock.” For the rest of her short life, Ulrike lives with that - the feeling that space and time interlock. The knife in the back “The political concept behind the dead section, I will say it straight out, is the gas chamber” Ulrike writes. Later, when Ensslin experiences it, she comes to the same conclusion: “The difference between the dead section and isolation is the difference between Auschwitz and Buchenwald. It’s a simple distinction: more people survived Buchenwald than Auschwitz. Those of us in there, to put it bluntly, can only be surprised they don’t spray the gas in.” Alone, acoustically and physically isolated from all the normal activity of the prison, isolated from other inmates and also from other RAF members as more are arrested, she even, on occasion, speaks to the wardens despite the RAF rule against so doing. But she has time on her hands. Lots of it. She reads, especially Brecht and especially Brecht’s play The Measure. She watches the events at the 1972 Munich Olympics unfold live on television, and reflects on the state of Germany in relation to Palestine and Israel as a result of the Nazi hegemony. (Her conclusion is that the actions of the Palestinian Black September commando are not merely anti-fascist but are even more so because they take place in West Germany.) For a while, she writes to her daughters, Bettina and Regine. This one, for example, in the autumn of 1973: “I’m thinking about you a lot at the moment. I wish Granny would write and tell me how things are. Tell her that. And come and see me! And write to me – do! Or paint me a picture, will you? I think I could really do with a new picture. I know the ones I have inside out. I don’t think my idea of getting you to say what you call me now was a good one. I’m just Mummy, your Mummy, and that’s it.” But by Christmas, she has broken all contact. She stops answering their letters. She returns gifts, including an Advent calendar they had made for her. It was Ensslin who had persuaded a reluctant Ulrike to abandon her girls originally, and Ennslin arrives at Ossendorf jail shortly after that Christmas. They are put in adjacent cells and allowed to see each other for brief periods. But this is for a couple of months only. Meinhof and Ennslin are the first members of the RAF to be transferred to the high security Stammheim prison in Stuttgart. There is a strict protocol in Stammheim. Their cells, numbers 718 and 719 on the seventh floor, are to be double-locked 24 hours a day. The doors may only be opened if two male and one female guards are present. The cells are to be searched “particularly thoroughly” each day. The prisoners are to undergo body searches on an irregular basis. A female officer will check the prisoners every hour until 20.00 hrs. The prisoners are refused all community activity, “including church-going”. They are, however, allowed to wear their own clothes, to exercise for an hour and a half on the roof of the building, to take a bath twice a week “although not on Saturdays, Sundays and holidays”, and they were allowed to be locked in the same cell for up to four hours a day. How much this helps Ulrike is debatable, because when she appears in court in August, charged with Horst Mahler for their part in the escape of Baader, she appears ill, silent and subdued. When she does speak, it is in an expressionless voice, a monotone, betraying no emotion. But she speaks for forty minutes, occasionally turning to the audience to ask “can you hear me?”. She arouses more pity than support – “History to the defeated may say alas but cannot help or pardon” – and Stephan Aust quotes one journalist as follows: “Ulrike Meinhof speaks, mercilessly turning her sharp mind against herself. A self-made martyr, a self-elected Joan of Arc of proletarian internationalism, with no army behind her but the people who call themselves the RAF, a spectral image in her poor clever head.” She ends by announcing that RAF prisoners are to launch a hunger strike in support of their demands. This is not the first hunger strike. It is in fact the third. But this time there appears to be a new determination. Andreas Baader: “I don’t think we shall call off the hunger strike this time. That means some people will die.” And Gudrun Ennslin: “Hunger strikes are a weapon only when it is clear they will go on until the collective demand has been met – even if it means illness and death.” I say “appears” because, in fact, Baader, Ensslin and Meinhof all take food on a number of occasions. Only one member of the RAF refuses all food. And that is Holger Meins. When he dies, on 8 November 1974, his six foot frame is skeletal. He weighs 6 stone. The day before, he has contacted his lawyers. “Please send someone, and quick. I shan’t be leaving my bed again.” But it’s Saturday. His lawyer is not allowed into the prison. Eventually, Judge Prinzing (who is to be the presiding judge in the forthcoming trial of the group) gives permission for the lawyer to enter the prison, but refuses permission for an outside doctor to visit. And it’s Saturday. The prison doctor is away for the weekend. His deputy? He has no deputy. The lawyer, Siegfried Haag, waits in the administrative area. Two prison officers carry Meins on a stretcher. Haag sees immediately that the message was no exaggeration. Later, he recalls the scene: “When I saw him lying there on the stretcher, I knew how things stood. I put my ear close to his mouth; that was the only way I could hear him … The visit lasted two hours: one reason it was two hours long was because I realized this was his last conversation, and he knew it too.” Meins whispers, “I’m finished. It’s over. I’m dying.” And finally, in a symbolic moment, asks for a cigarette. Haag lights one and places it between his lips. When Haag leaves – he has already overstayed his allowed time – the prison guards panic and call in a doctor. But by the time he arrives, at 17.15 hrs, it’s too late. Holger Meins is dead. We’ve talked about the strict protocol which the authorities had imposed for the keeping of the prisoners. It also imposes some regulations on the prison and the prison officers. In this case, the regulations are clear that the prison doctor and the prison governor should have informed the Ministry and arranged to have Meins admitted to the intensive care ward of the hospital. They didn’t. In Stuttgart, within moments of the news of the death being announced on the radio, hundreds march on the residence of Judge Prinzing. Other marches, just as quickly, take place in Frankfurt, Cologne, Hamburg, Berlin and Stuttgart. If Ulrike had presented herself as a martyr at her trial in Berlin, the RAF now has a genuine martyr. Between 1970 and 1972, the police were searching for maybe forty people. Now, they are after 300 or more, with police estimates of ‘sympathizers’ numbering over 10,00. Only when in prison do they receive this level of support. But inside the prison, with all key players now in Stammheim, all is not well. Baader and Ensslin are back in charge, Baader acting as leader, Ensslin attempting to maintain discipline in a series of circular letters. Often, Ulrike is the target. Stephan Aust is a good source for many of the political or perhaps gratuitous communications which are exchanged between the prisoners on the seventh floor. Baader to Meinhof: “But of course you’re one of those liberal cunts … you’ll liberate yourself only in the fight, and not by whirling around yourself in the fight like a spinning top. And of course what you’re producing does it no good either …”. Ensslin to Baader: “Ulrike, if you want to know, really gloomy: a vampire, quivering with blood lust.” Baader to all the women (he calls them the lady’s maids): “That simply doesn’t need any further elucidation, it’s in every step Ulrike takes, everything she does, and betrayal is only a word for it.’ But the bitterness reaches its peak with this exchange, of which we only have Baader’s side: “It’s hatred, then – don’t fool yourself, you hate us – there are any amount of signs of it, which naturally, oh so casually, and at the vital moment give rise to passivity, self-withdrawal, the wrong sort of language and content, destructiveness, misunderstanding. The problem is that you, and the others, have now become a burden, you’re appallingly disorientated pigs. I’ll have nothing to do with what you call self-criticism, and you needn’t think I must. You’re the ones destroying us – something the law could never do.” But here’s the killer line. Ensslin to Meinhof: “You open the door to the cops. You are the knife in the back of the RAF, because you never learn.” Stammheim Stammheim is now, in every sense, the centre of the RAF. At a cost 12 million DM, a special high security courthouse – “a memorial of steel and concrete to them in their lifetime” says Stephan Aust - is built in the grounds of the prison. Here, the first generation of the RAF in the form of the five members officially identified and indicted for five murders – are to be tried in a trial which will last for two years and which is notable for a succession of provocations from the judge, the prosecution and the defence. We’ll come to those in a moment. 1000 witnesses will be called; 70 ‘experts’ heard; And the prosecution produce more than 170 files, amounting to nearly 100,000 pages. The files are named “Baader – Meinhof – Complex”. It is a ‘show trial’ in the sense that it is a spectacular courtroom drama. And it takes place in the context of the second generation of the RAF, many of which are unknown to the first generation defendants, embarking on a series of actions which far outweigh anything attempted or achieved by the first. A judge with no connection to the trial is killed. Berlin mayoral candidate Peter Lorenz is kidnapped. The German embassy in Stockholm is invaded, two diplomats are shot, and a bomb detonated that destroys the building, killing two and wounding several others. Jean-Paul Sartre visits Stammheim in December 1974, but makes it clear that he is not there in solidarity with the RAF’s political stance. “This group is a danger to the Left. It does the Left no good. One must distinguish between the Left and the RAF.” (Baader’s recollection of the conversation is succinct: “As for him, what I got was the impression of age”.) Nevertheless, it is true that although the militant Left as a whole is increasingly concerned by actions of the second generation, there is solidarity for the first generation as they take on the full legal apparatus of the state. Restrictions are placed on legal advisers. Listening devices are placed in the prisoners’ cells and in those rooms where they consulted with their lawyers. The judge himself is revealed to be leaking information to Die Welt, a conservative newspaper. When the outbursts and arguments of the prisoners, the prosecution call in the state to assist them. The Bundestag passes a series of special laws which restrict those who can represent the accused (one lawyer is banned because he calls himself a ‘socialist’), and also allow the judge to continue with the trial in the absence of the accused. This is significant because of a recurring theme of defence motions is that the regimen under which they are imprisoned, which the judge has refused to relax, makes them unable to stand trial for more than three hours a day because of poor physical and mental health caused by the conditions of their incarceration. On Day 39 of the trial, 23 September 1975, three medical experts give their verdict on the prisoners’ health. They are suffering from weakness, disorders of speech and vision, under-nourishment and loss of weight and poor concentration. Ulrike is unable to concentrate at all. But two days later, Day 41, she asks the judge: “How can a prisoner kept in isolation show the authorities that his conduct has changed?”. She answers for him: “The prisoner has only one possible way of showing that his conduct has changed and that is betrayal. “That means that in a situation when you’re in isolation there are just two alternatives. Either you silence a prisoner, by which I mean he dies, or you get him to talk. And that means confession and betrayal. That is torture, that’s nothing less than torture by isolation.” It is a very personal statement, and it reflects her state of mind. She is not alone in suffering depression – several others can only sleep with the help of strong sleeping pills given to them by their guards - but in her case, it is more marked and more profound. She never recovers from that year alone in the dead zone of Cologne, and once in Stammheim, living in what has been described as a “bizarre collective, watched over by a squad of guards”, she is in the final stages of a gradual nervous breakdown. There is no support from her comrades; rather the reverse. As we have seen, her relationship with Gudrun Ensslin is at the heart of her increasing self-doubt and self-loathing. The tensions are political and personal. Political as Ensslin criticizes her stance on Black September and the ending of the hunger strikes; personal as Ennslin accuses her of feigning her mental state in order to shirk responsibility for her and their actions – “you want to crack up” she says; both personal and political as her attempts to write RAF manifestos are rejected contemptuously by the others. This is when she begins to distance herself, to withdraw into herself. She needs to make sense of, to justify, their actions but she is unable to do so. the occasional rant in open court only emphasizes the 24 hour a day depression she suffers as, in the words of Robert Storr, “she became a victim of her own totalizing beliefs; revolution had consumed the whole of Meinhof’s identity, but, ultimately, there seemed to be no place in the revolution for her.” “How am I ever to find myself if I’m forced at the same time to coexist with the horrible image of me she (Ensslin) has in her head?” writes Ulrike. To which Ensslin responds in a note in the margin: “Projection, paranoia, swine.” On day 106, 4 May 1976, all four principal defendants appear together in court. It is almost four years to the day since the attack on the Springer printing works. Seventeen people had been injured and Ulrike Meinhof had written the letter which claimed responsibility. But Gudrun Ensslin in court makes a statement in which she refers to the operation “against the Springer building, of which we knew nothing, with the principle of which we do not agree, and which we disowned while it was in progress”. However vicious and bitter are the disputes and tensions internally between the prisoners, their solidarity in public is total. Until now. This calculated disassociation, this conscious breach of solidarity, is perhaps the last straw. On Sunday 9 May, at 07.34 hrs, two prison officers open the door to Cell 719. Ulrike is hanging from the grating of the window. She is facing the door, having fashioned a noose from torn bed sheets and, for a second time, taken a leap into the unknown. Uncharacteristically, for one who defined herself to a large extent by her writing, she leaves no suicide note, no farewell, no message of encouragement or recrimination. This is one of the points raised by those who argue that her death is not suicide, but murder, assassination, execution by the state. But Stephan Aust points out that, some months before, she had written in the margin of a paper on strategy, the following: “Suicide is the last act of rebellion.” |